21 November 2023

Craft as Subject to Chance

Notes on Craft

I’ve been starting these conversations by asking folks to introduce their primary profession and whatever creative pursuits might be intertwined with that. It would also be great if you could speak to any tension that exists in this interplay.

Jonathan Mark Jackson

I suppose there are meta levels to how I think about my practice. There's the obvious front-brain action of making the photographs and being out in the world and present in certain spaces or at specific events, and taking those moments to construct images with the camera. But the thing that actually takes up the majority of my time is teaching, and that’s mostly instructing on the practice of using specific cameras and making photographic images. I also have this side gig at a digitizing post-production company, where people go to get their family or institutional archives scanned and digitized. A lot of that work has actually turned out to be re-capturing photographs with a camera. And I've been very interested in this act: using a camera, not so directly by going out into the world and finding your image, but purely for the act of replication and digitization. Those things are kind of primary to how I think and make and work these days.

What do you feel is your relationship to balancing all of those things? With teaching being so primary, do you find yourself wishing you had more time to create—how do you feel all of that lives in tandem?

Teaching is definitely work. It takes up a lot of emotional energy. I'm always exhausted by the end of my classes, but the work feels more like a duty I have to fulfill rather than something that I’m doing for the check. It’s become a much more fluid way of working, I think. Of course, I’ve realized that the expectations and the fluidity you feel can vary from school to school, that each place is really different from the next. Art schools and art conservatories are especially unique places.

After RISD, I was really ready to be theoretical in my teaching, and I had to pare down a lot, and go back to the basics—you know, before we get into continental philosophy, you have to know how to use this tool. After that first semester on the job, I realized just how much I should be defining the learning outcomes for each class. And my classes are now very instructional. Whether or not you're gonna be an artist, I will teach you how to use this camera.

So in an interesting way, I spend the majority of my time making photographs and thinking about photographs, but much less pursuing my personal work. I’m teaching and working this other job and imagining images. And when I make things, it’s in these short bursts of time over the weekend or whenever I can manage time away, mentally and physically.

Do you feel like things come more easily because of that, perhaps in relation to the kind of belaboring you did throughout your time at RISD or prior to that degree? Are you ever surprised by how much you can make in a quick turnaround because of the ways you're consistently absorbing content, even though it feels like you might be doing so passively?

My value system towards time is definitely different. But I find the limitations to be helpful because you just have to make a choice, you know. If I procrastinate or if I am waffling on something over one weekend, it'll take me two more weeks to get back to that same place. So it's made me more forceful, in a way; more decisive. I just have to make the choices faster.

It's kind of romantic, a spiritual experience, in a way, to look back and see that it’s taken 200 years for me to be the one to construct the image or hold the camera. And in other ways, I realize I might just be constructing myself.

Your talking about teaching in such a technical manner leads me to a more direct question about craft. How much do you relate the technical exposure to a camera to a form of craft or do you think about those things differently than you might other traditional trades?

I was thinking about this as I was driving home this afternoon, asking myself, “What is craft, really?” And I think, initially, I found myself conflating “craft” and “practice,” kind of unable to differentiate the two. They feel very close to me. The persona of a photographer or a designer or a painter is very much rooted in practice—it’s the thing you steward your mind towards doing everyday; it’s the way you show up for the work. But craft has a connotation that implies something manual—things made by hand—and typically, the production by hand of an object. More often than not, the act creates something physical.

Photographs are a little confusing because they're both objects and not. I shoot on film so there is a negative and a careful handling of that negative until it's developed, and digitized or printed. There are stages that take place in the process of the image becoming an object, but those progressions are slow, and less definitive. That process is definitely much less direct than what you might see in traditional crafts.

And still, I understand that I have distinct relationships to particular cameras similar to how a craftsman might relate to their specific tools—there's a small camera and a big camera and the small camera makes me work differently than the big camera. I think there’s something there about how the camera itself shapes the photographer or the maker's body. All of this has me thinking about craft here in New England, and how I associate many of the craft artists in this region with a quality of handiwork that produces basic utilitarian goods. I also find that many of them are socially engaged, even in some cases, political actors, historically using their crafts to translate messages to the public. This means that these individuals often make in community. Somehow, I think this might distinguish them from other makers.

This collective element is something I've been asking folks about a lot and whether their craft was somehow absorbed or inherited through familial traditions. Even though it sounds like you might be resisting defining your own art as craft, I wonder if there’s an element of this that you relate to. Can you point to any familial traits or habits you feel you might be emulating? Or maybe better put, what are the threads can you pull at to trace your creative trajectory?

There is a group of photographs that comes to mind—I actually hate the term “body of work”—so I’ll call it a group. I produced these images for my undergraduate thesis. The photographs were taken inside of a house where one of my ancestors lived and worked as a domestic servant, in Waltham, MA of all places. His name was Robert Roberts and he wrote a book about it called the House Servant's Directory which is really a book about craft. It gets at this tension between craft and practice, actually. It was written and published in 1827, at which point the book acted as a guide to others—those others being free black people in the region looking to become domestics. It covers everything from cleaning to behavior and etiquette, to dress—it’s a very thorough text. His place of work is a preserved home now, which led to my own work and a series of other discoveries along the way.

I suppose, what feels like my own inheritance from this ancestor I didn't know growing up is this keen sense of observation. We somehow share a propensity to observe, look, and study. This characteristic appears multiple times throughout my family. My grandfather was a photographer. And most before me seem to have been observing the world closely, but often lacking the resources to realize those observations on a grander scale. That’s one way that I think about inheriting this medium—it’s kind of romantic, a spiritual experience, in a way, to look back and see that it’s taken 200 years for me to be the one to construct the image or hold the camera. And in other ways, I realize I might just be constructing myself.

What do you think drives that self? Is it the desire to document or instruct, or is it typically more abstract than that? And how are you typically able to find those anchors?

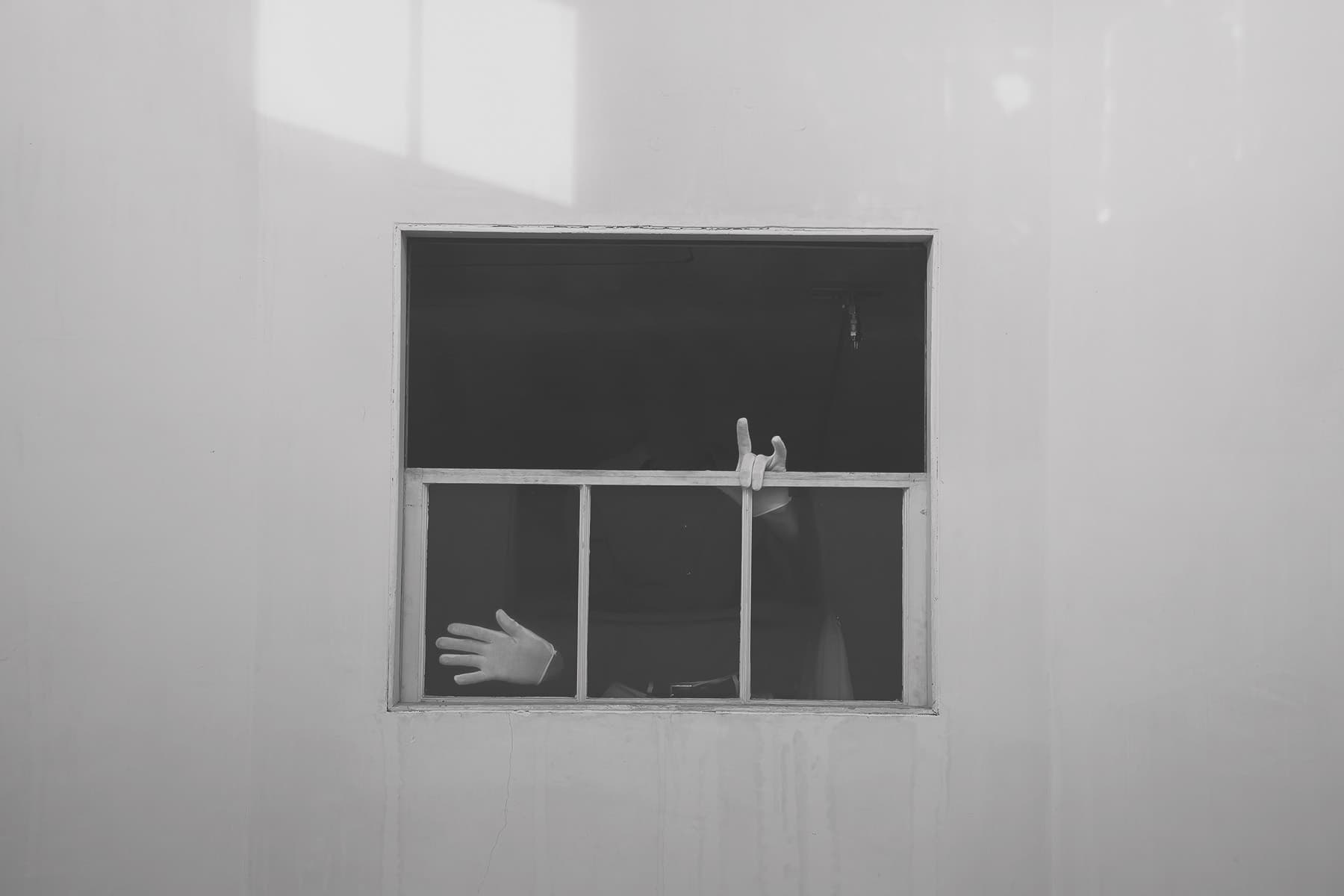

When I take photographs, I try to be direct. I try to point the camera at the thing. It’s not risky stuff, photographing still lifes of objects and whatnot. But as I’ve grown into this medium, I’ve begun to notice a certain quality of interference in those attempts to be straightforward. There’s something outside myself that makes the pictures somewhat mysterious or veiled or abstract.

I'm putting together a new show for the coming spring, which will feature a collection of images I shot thinking, “I’m being a documentarian. I’m going to the park with my camera and taking it to various events. I’m capturing a moment.” But as I'm putting the images together, they all feel very elusive. They don’t feel at all like the moments in which I shot them. I definitely think of myself as a formalist photographer—I'm not so into messing with the shape of the thing or the presentation of the thing. But the content always holds some mystery despite that.

Sometimes, there are descriptions from novels or poems or visual metaphors that end up feeling like direct ideas for constructing pictures. I write those down too. I make these lists and I wait to see if they arrive in the real world, more spontaneously, or out of chance.

That’s interesting—almost like someone else’s hand did the work. I want to reach back at something you mentioned earlier about handling your negatives and the loss of control that becomes possible there. Craft is often associated with a sense of control over variables, but simultaneously with the presence of the hand. Is control something you aspire to in your work? Does releasing yourself from that make you more present?

I think I feel the most present when I’m controlling the variables. Whether that’s with portraits or still lives, there's always something I try to alter or adjust in the scene. With objects, I like to handle things first, to test their weight, to see how they might balance on others, to counterweight them; I challenge them to stand on their own or scaffold them, as if in a boutique. That process is very free-flowing—it’s almost like I have no thoughts during those exchanges. And with people, it’s somewhat similar. I move bags out of the way or ask individuals to take off their glasses; I adjust things so that the image feels a little bit outside of how I previously found it.

Certain variables also factor into the making of the photograph—you control the aperture and shutter speed, which have these optical effects that you almost have to imagine before you can actually see their effect on the final image. I would be a bad photographer if I didn't mention that there are actually technical controls that alter a picture.

I've been talking to people a little bit about the idea of craft as durational. Our sensibility of it can be entirely contingent on the fact that the final output appears to have taken a lot of time. I guess I'm more interested in time’s relationship to the part that precedes that—the idea part. The question being: As ideas come into your midst, do they evolve over time? And if you wait too long, do those ideas lose their importance? What is your relationship to ideas and how do you manage them over time?

It’s a terrible feeling when you have an idea for an image and know there’s just no way to get it out or find it or execute it. Or what you’ve imagined just fails to take place as seamlessly as you hoped. In the moments after I’ve worked really hard to stage a photograph, something often becomes amiss. I've been thinking about this a lot recently in photographing people. It's a different way of working—to hire a performer or an actor or to contract someone into making an image with you becomes something very different. I have a secret writing practice, or maybe not secret, but a writing practice that's just not that big a deal. And I’m very into making lists; I make lists of turns of phrase that come to me. Or sometimes, there are descriptions from novels or poems or visual metaphors that end up feeling like direct ideas for constructing pictures. I write those down too. I make these lists and I wait to see if they arrive in the real world, more spontaneously, or out of chance.

There’s this park I've been going to in a suburb of Boston, called Jamaica Plain. There’s an arboretum there, owned by Harvard. And over the summer, I was going there once a week to photograph. It was the summer, so of course, it was always really lively. I was looking at these Seurat paintings at the time and I wrote down in one of my journals something like, “I want to photograph an impressionist scene, someone sitting in the grass lunching, or someone just leisuring in the park. And everytime I went, I would think about that.

So there was one afternoon when a thunderstorm started rolling in. And there were very few people in the park. And I saw this woman sitting and meditating before it began to rain. And in that instant, I just thought, there's the picture—there's this thing that I've been thinking about all this time. So I approached her and made the photograph. And it turned out that she was there celebrating the one year anniversary of her breast cancer removal. So she was in her own internal state, having a kind of spiritual or meditative experience. And I don't know, the fact that our stories overlapped for that single moment in the park means that I now have this picture and a document of the encounter. It’s definitely not a very efficient way to execute a concept. But I also feel like it had to be that way. Even if I don't describe that anecdote to people, I think the picture feels more resonant because of the instantaneous overlap, my looking and her being there.

Right—it wouldn't have been the same if you had staged the idea and it also would have been equally different if there wasn’t something in particular you were looking for. It’s funny, I don’t know that my work functions that way at all, at least not as it concerns the production of images. I suppose it’s more common in my writing practice—sometimes you're reaching for something, a feeling maybe, and then all of a sudden, you see something that allows you to communicate it more completely.

Related to this encounter, I wonder how much you think about the public recipients of your work. And in doing these portraits, do you feel like the image ends up being for them as much as it is for you or is there someone else altogether that you have in mind?

I feel very selfish in the way that I've been working. I’m sort of interested in photographing other people like me, or people I feel are kind of similar to me, which is namely Black people in New England who are sort of doing their own thing. I have a lot of history in this region, but I’m also more acquainted with rural, provincial life. Living in Boston has opened the work up to new encounters. But the individuals in my photographs are still by and large members of my family or strangers whose existence seems to have some kind of historical association with the Black experience or a reference to my own narrative. When I make these pictures, I initiate a conversation with the people I encounter. I'm honest—I say I'm an artist and that this could appear somewhere in public. And if they are willing to be photographed, I take their contact information. I ask if they want to have a second shoot or meet another time and honestly, no one has followed up on that second meeting. So it can be tough—I have these pictures as both a document of these moments, but I still feel like a bit of a student. I’m still trying to teach myself how to really make pictures in this way, that feel effective and meaningful. And I don’t know that I have an intended audience—it still feels like the beginning stages of something.

I have this assignment that I give my students at the start of every class. It’s a little Yoko-Ono-esque—I have them take a walk for an hour in one direction until they get lost and then walk back in the same direction. So they have to commit two hours to walking. For many of them, it's their first time going out with the camera. So I don’t offer any guiding principles—I don’t have them photograph something in particular, or think about composition, or pay attention to scale. I just want them to walk and take pictures as they go. It’s something I’ve always found refreshing to do myself. When I’m in the rut or in the weeds with an idea—the results are usually just pictures of trees and branches—but sometimes you find the golden ticket to the next big thing. At the beginning of something, you just have to keep moving. The meaning always comes.

After we get off the line, I'm going to make a bunch of pie crusts and I’m thinking more about the preconceived ideas we bring to acts like this. I know how to make pie crust. I've made so many pies, but inevitably the crust will be different than how I imagine it. There’s something about that, which maybe people in traditional craft trades feel too—they know how to do it, like I know how to photograph. But something always takes over once it leaves your hands.