6 November 2023

Craft as Permanent Impermanence

Notes on Craft

I’ve been starting these interviews by asking folks what they do as their primary occupation and what they would consider their other creative habits and pursuits.

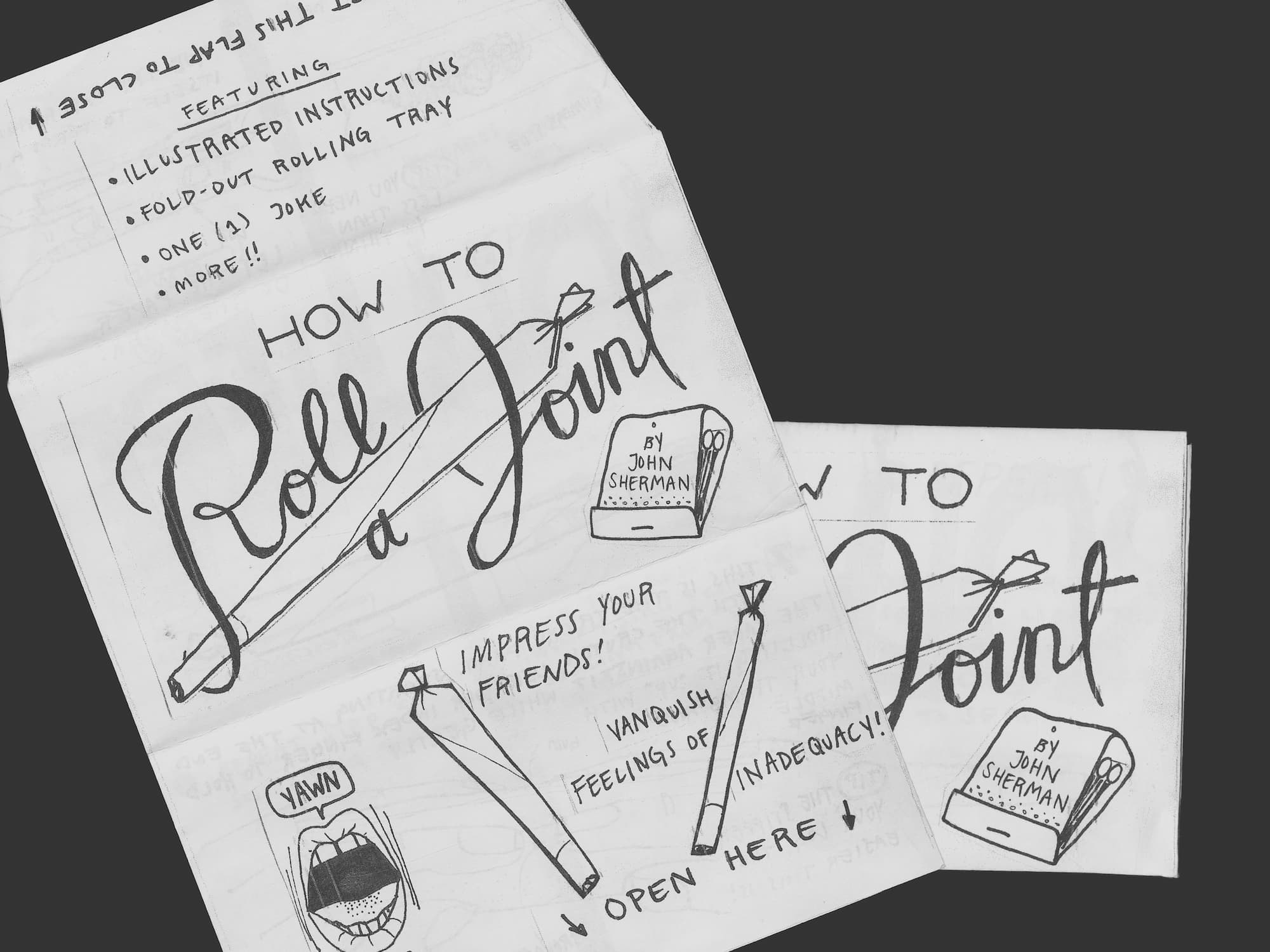

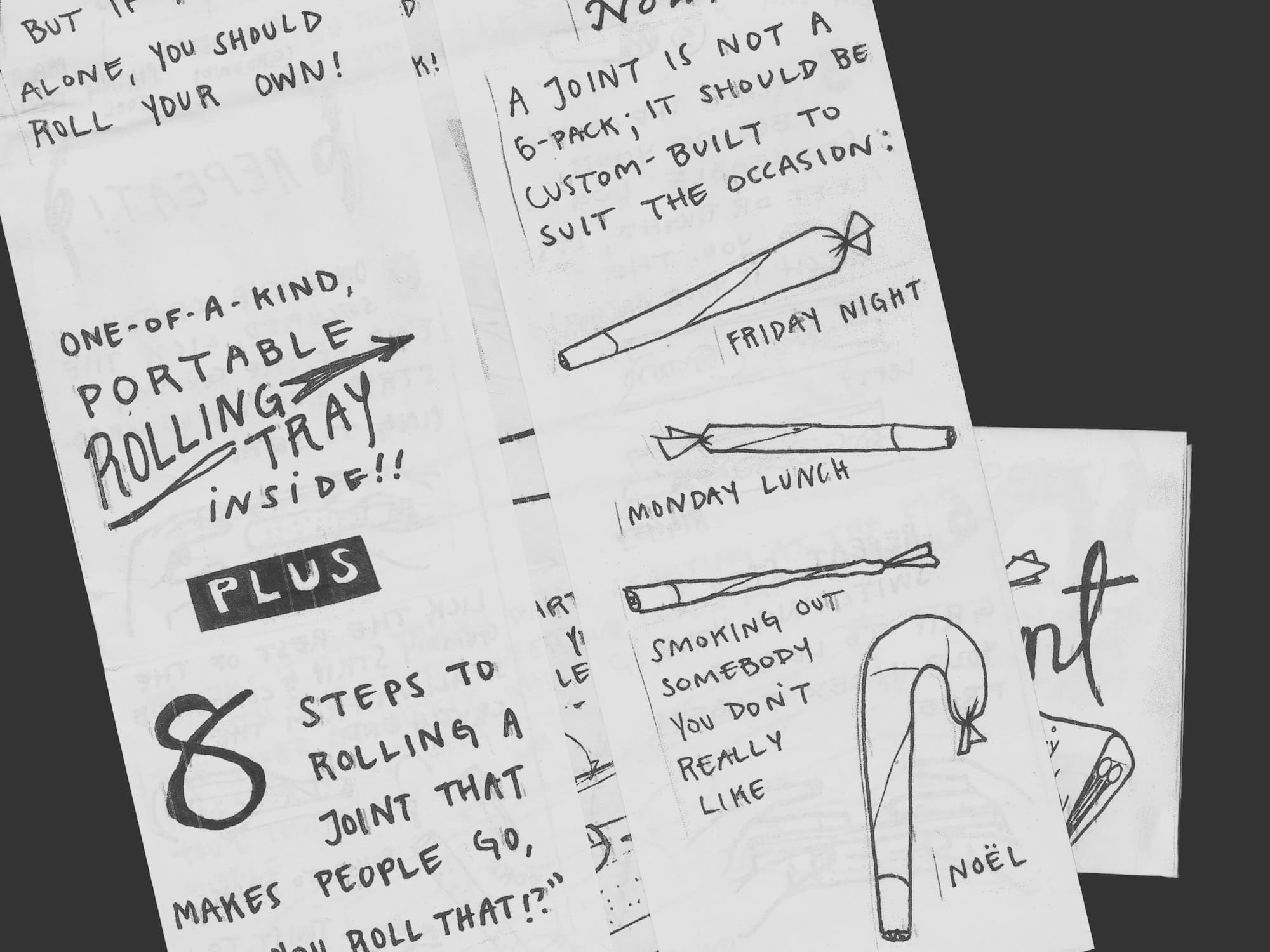

John Sherman

At this point, I think I would say that I work as a typesetter—I actually don’t know how many typesetters there are left in New York—maybe fifteen. I haven't met any of them. Or I’ve met maybe five, but seriously there aren’t many. I also do proofreading. The corrective arts is what I would maybe call these things. It's all just kind of exacting stuff for a magazine.

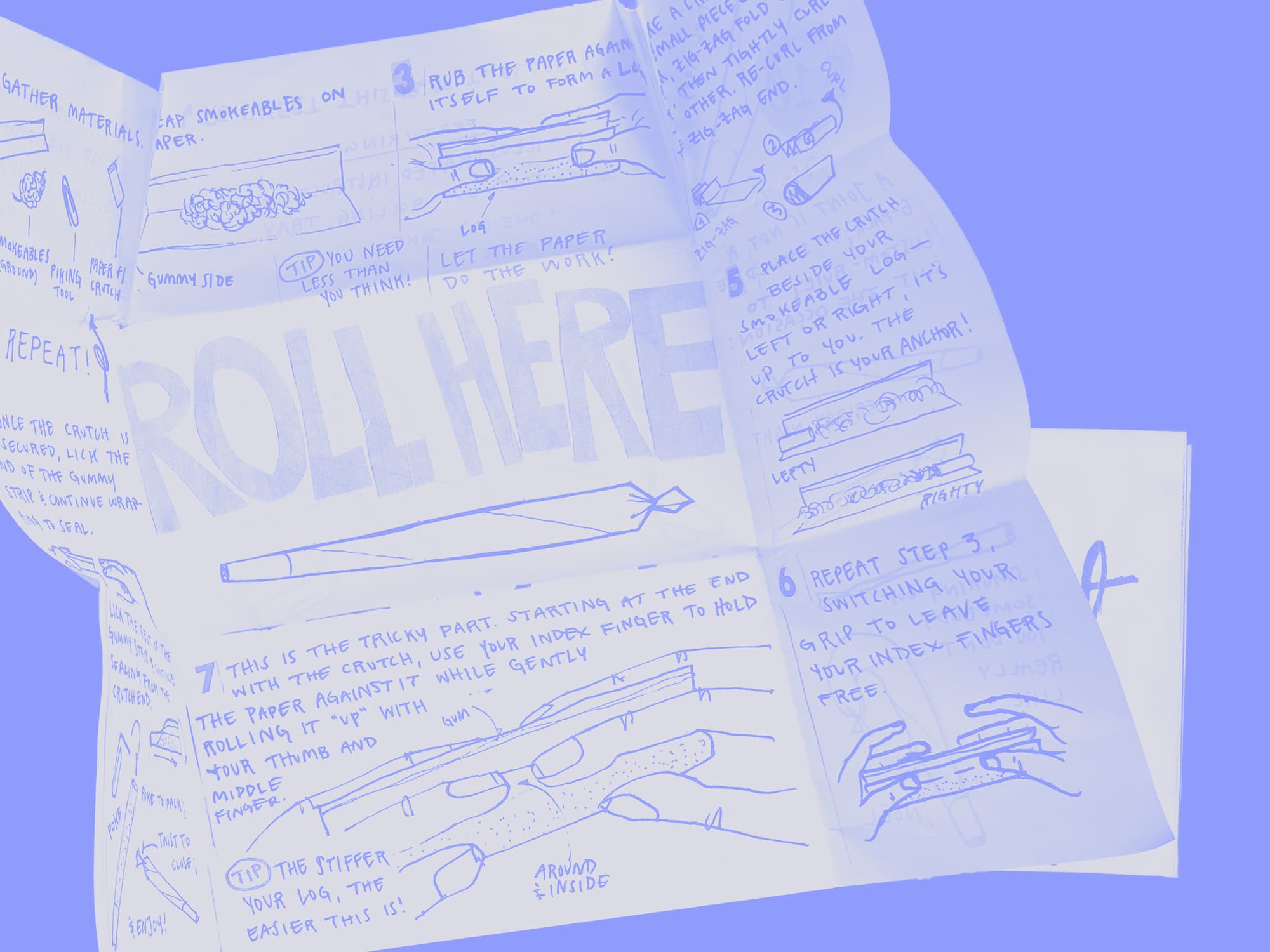

The other thing I do lately is cartooning and zine-making. It’s not informative. It's not spell-checked. It’s grown into this opposite force against all the correcting I do in my day job, where I have to make sure that everything is perfectly lined up. That work is so much about fixing things and correcting things and running a ruler down everything and making sure there is no sign of anyone. The best I could do my job is to have no one even think it's typeset. The same is true of copyediting or factchecking—you’re invisible and that’s a good thing. And so that's why the rates are so low—because no one knows that we exist. But no, my zines, they just feel like I'm passing notes under the table at dinner and nobody realizes, you know— “I'm just doing my job over here.” It’s honestly not that subversive; it’s just been a way for me to resist seeking out any of the things that come with being a respected contributor to a magazine.

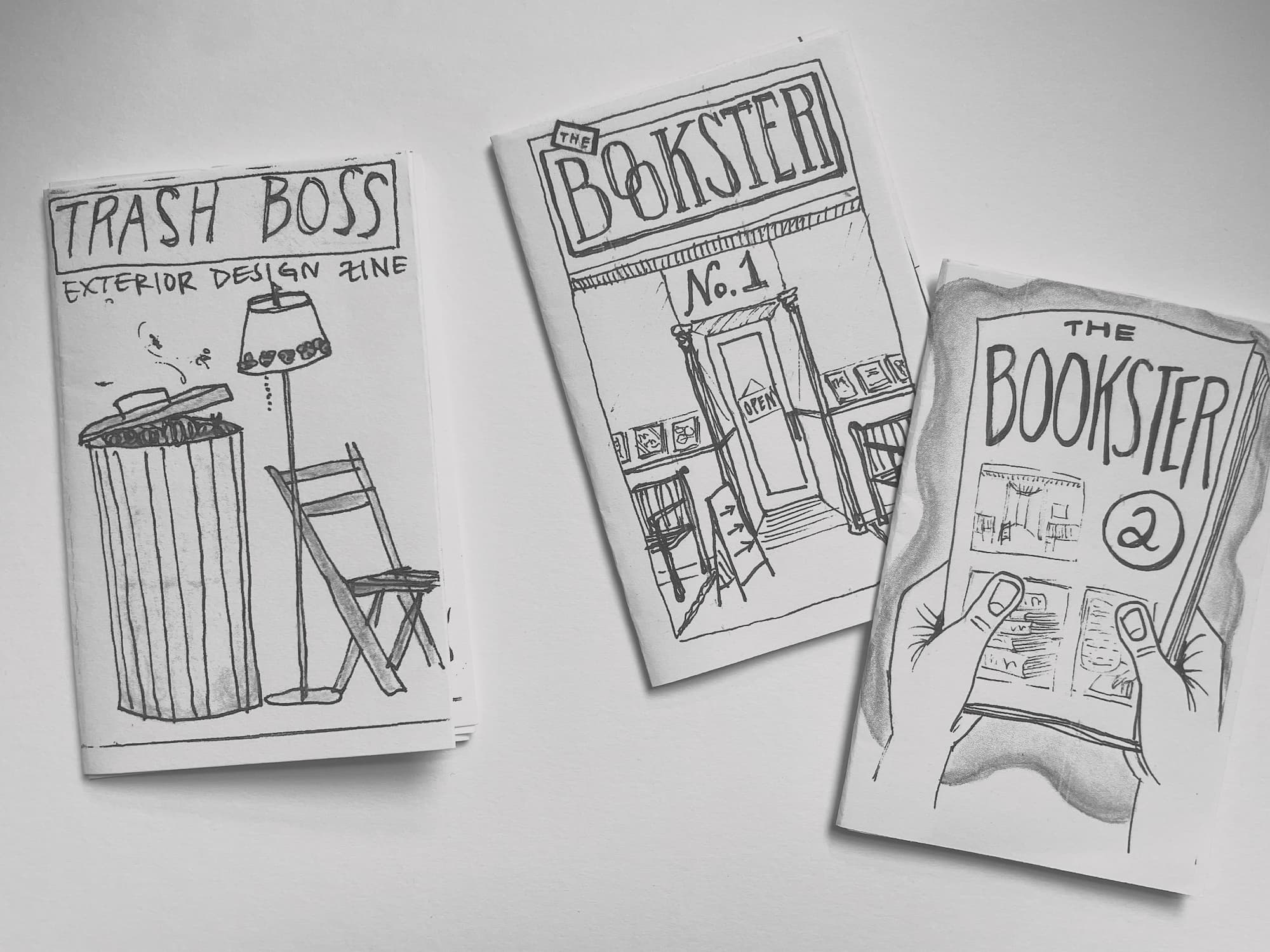

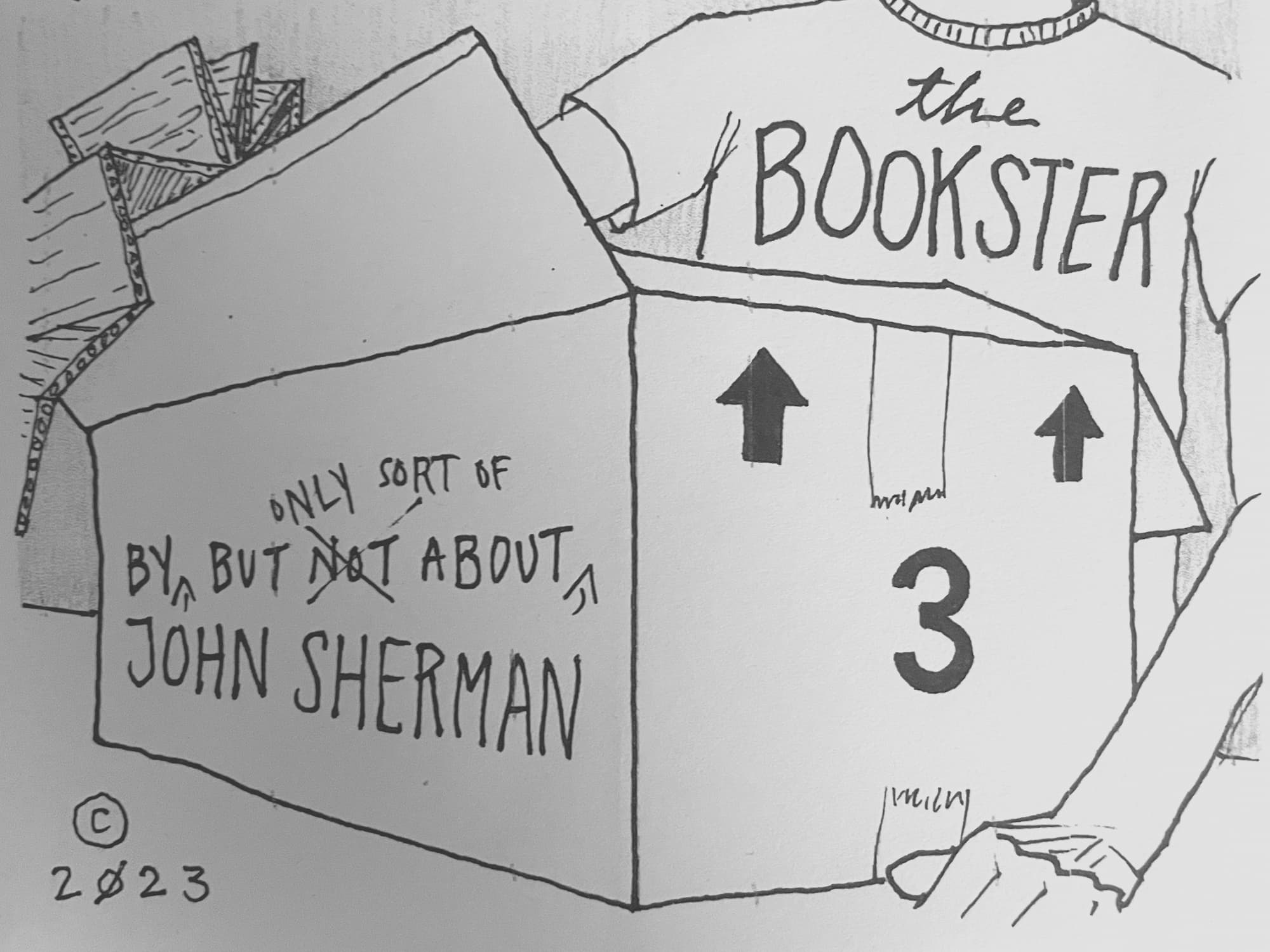

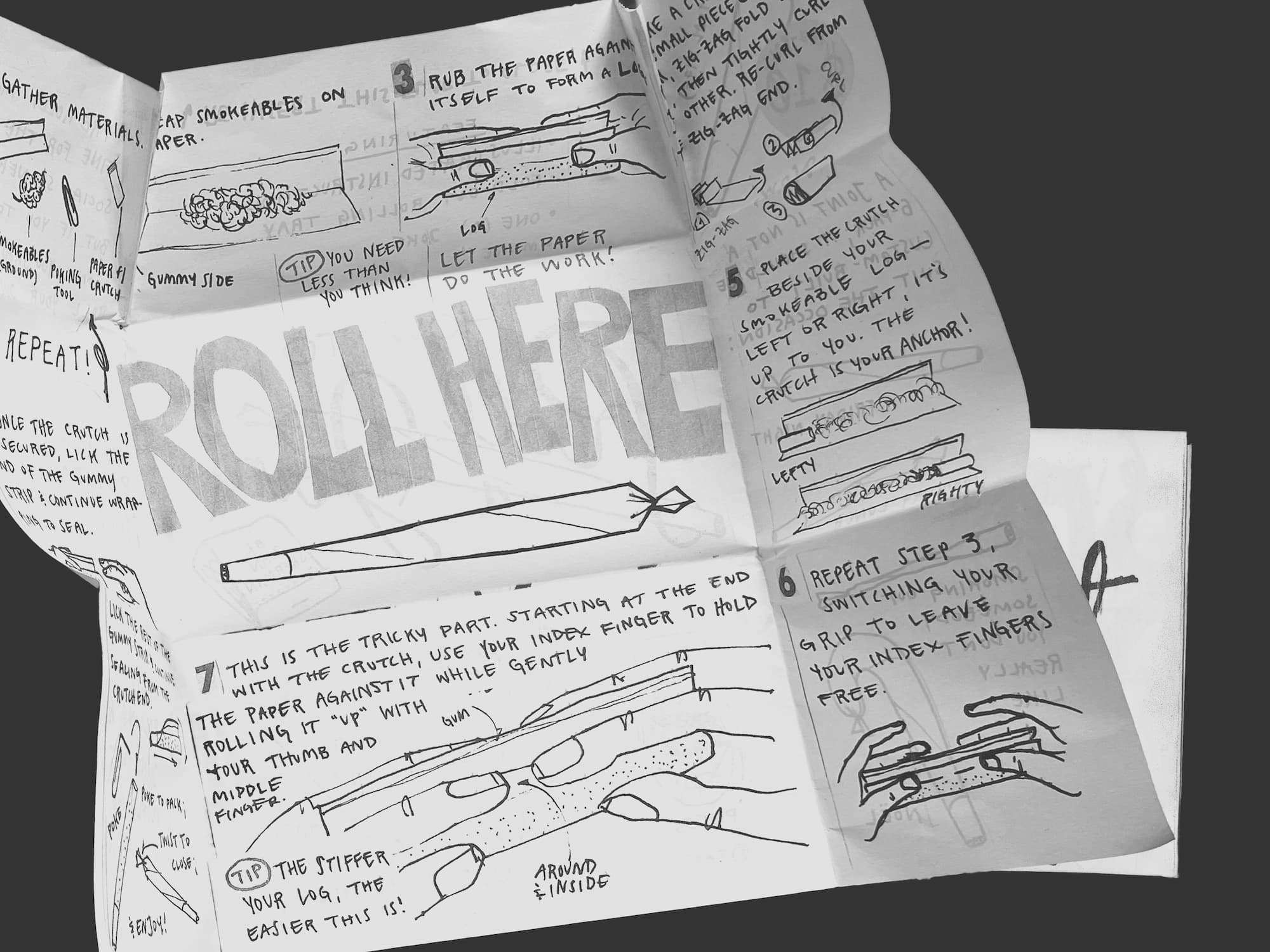

Now, I really like when you can see a thumb smudge in the tape; I think it’s almost proof that it's been handcrafted. I think that's one of the things I've really tried to lean into—that’s led me to making mini-comics or things that don't have to rise to the level of a project. It's just a single page or a little character I drew, and whatever I do with those things, it almost just feels like an exploration of what ifs—what if it's supposed to say this or that, or what if it lands in a wildly different place. It’s mostly reproducible visual, handmade stuff that I sell here and there. Some of my little comics are housed in bookstores. Two of them, “The Bookster” and “Trash Boss” are for sale at Bluestockings in Manhattan. It all just kind of floats out into the world.

How has that work made it into the world so far?

I haven't even brought them to the location—I’ve just mailed them in through the open submission link with a note. There’s otherwise no website for this content—I don’t put them online; I don’t have an instagram. I just want them to be something that somebody can have a random experience with, just like something you find on the street, where you have no idea of its origins, but you get to stop and really look at what you’ve come across. It’s been satisfying to remove myself from content. I suppose I’m a little more interested in authorship now.

But yeah, mostly I have an analog existence in the world and then I just give things to friends. And if I give them extras, they can give them away to somebody else.

And in what ways are you thinking about authorship now?

I've been interested in finding work that other people have done under various names and why. I was reading about some cartoonist—I think it was Jay Lynch—he worked at a newspaper, as I recall. Anyway, he was doing cartooning for underground comics and he just changed his first name so that he wouldn't get in trouble with his other job. Somehow, he figured that would be enough of a change to cover his spot and still leave room for ownership. So even little tweaks like that are interesting to me, because they aren't necessarily obfuscating too much, like building a brand might be—I don't know if that makes sense. Finding a drawing with an entirely different name on it has a different effect on me. It changes my reading a little.

Whatever people's perception about a name or tagline they read, I realize this is something I can control and I'm actually interested in not controlling it—just placing some little doodle on the back and marking the territory that way. I have a couple of books that I’ve found over the years and I just love them. It's just kind of mysterious.

It’s kind of like adding another layer to the story without revealing too much about yourself in the process.

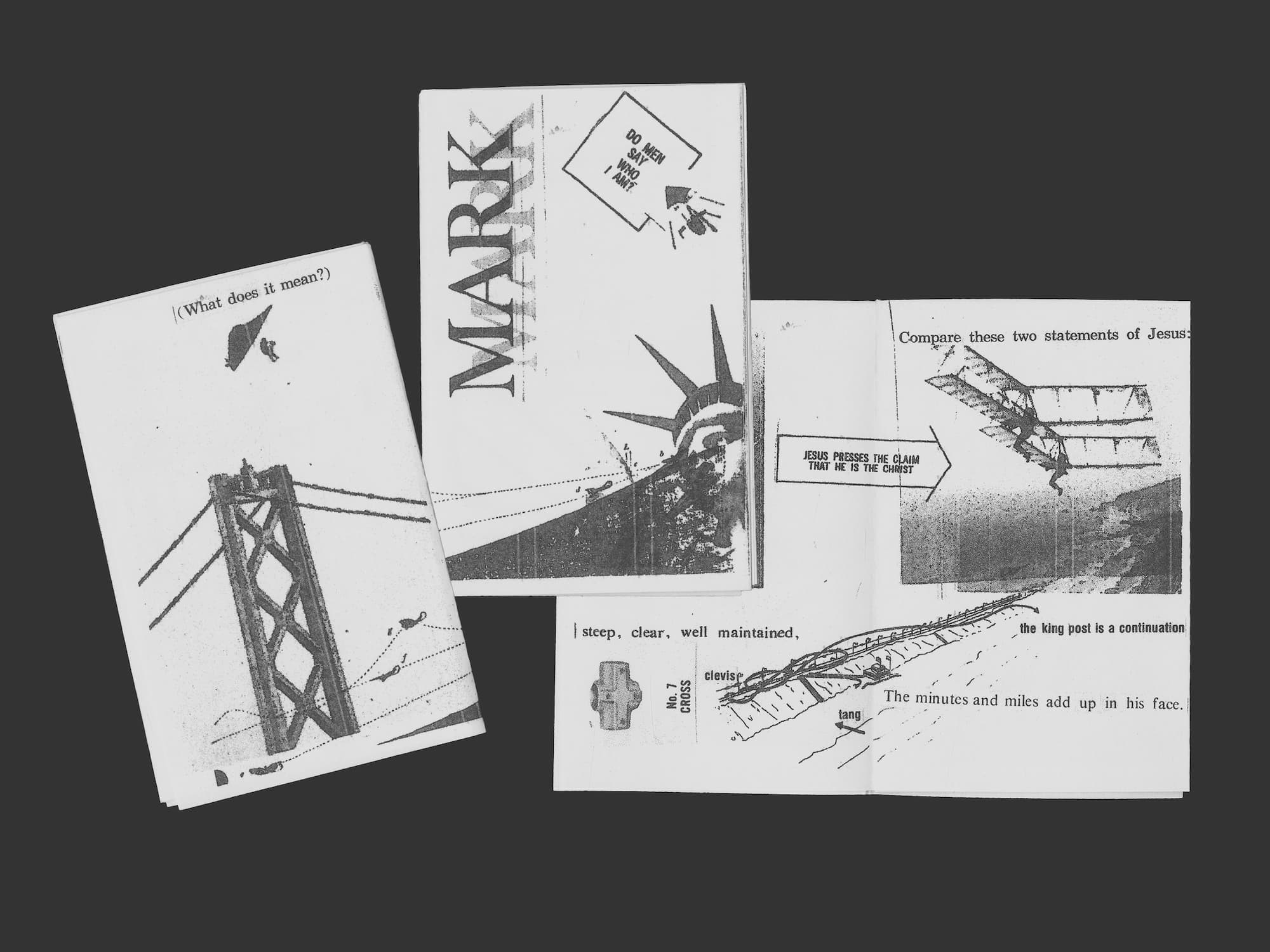

Right. Yeah. I come across religious pamphlets every once in a while. People stick it in my side view mirror or I find them on the ground or run into people standing on street corners, giving them out and I just love them because it’s just impossible to buy into any of them. The tone is always totally off the wall. Some of them are really shouting at you and some of them are just giving you a real whisper. They're like, “Hey, have you been thinking about something?” Sometimes it seems like it’s an organization that puts them out, but what I love about that is how little I know—the omniscience of that. This voice is just speaking into New York, or wherever you may be, and maybe somebody hears them and maybe changing their whole life because of it. To use that method to no end is kind of powerful. It’s sort of akin to anybody who draws a weird drawing on the sidewalk or puts stickers on signposts—it’s like free art. It’s all kind of in the same sphere.

It’s kind of like adding another layer to the story without revealing too much about yourself in the process.

Honestly, there is one that’s so well done that I can't even tell if it's joking or if it’s serious. I mean it seems like a complete spoof—there’s this little cartoon Jesus on it and speech bubbles everywhere. It would be so funny either way.

Hilarious—I guess we’ll never know. I'm curious how you came to zines as an output. Besides the pamphlets of course, what kinds of encounters have you had throughout your life, or maybe just more recently, that have inspired this way of making and translating?

I’m not sure exactly. I was always doodling in school, almost as a way of paying attention. And actually my grandmother was an artist. And she always used to sit by the phone doodling. She had this little pad of paper, where she used to write down numbers or what-have-you, and on the margins of every single page, there were little mountains and little hash marks. And I feel like there was just—art is the wrong word or maybe art is not the wrong word—there was just art kind of falling off of her everywhere, and the same is true of me. Just like crumbs, crumbs of your little work ending up on the fridge or wherever throughout the house. Maybe the doodles developed an ever-presence that way—these are things you can just give away or turn into little decorations. They are always there, but they don’t have to feel so precious.

You know, I did theater too and I hated that kind of attention. I mean, eventually. I liked to sing but I didn’t want anyone to look at me while I did it. And so, maybe that's actually the way that I'm approaching this—we can both look at the thing but I'm not necessarily next to it while you do. I don't know what that's about exactly. The output only has so much to do with me.

It’s about the challenge of emulating something, testing my capacity to draw something, a shape that I like, a form that’s complex.

Yeah, it’s your self expression, but you don't feel the need to stand up in front of it and say so.

Exactly. I didn't grow up with zines in my home, or anything like that. I think it’s just like in the last couple years I started looking out for that sort of thing. But I was certainly always reading comics—you know,“the funnies,” as my grandma said. That’s what she called the comic section of the paper. So that had a certain significance, but it’s also this disposable thing—that eventually goes in the fireplace. But you want to read it first.

I suppose that kind of life cycle is important to me—I don't think it diminishes at all. I think it's an experience you get to have, where you go, “Wow, I love that one today,” and then move on. You don’t have to hang onto it. That’s different from a lot of other crafted objects. I mean I love used bookstores but sometimes I walk in and I think, “Oh my god, these are never going to go anywhere.” Each one of these is so fascinating but all of this work is just sitting there, getting dusty. Not that my zines won’t hopefully end up in the same place, but at least it’s less paper to waste.

Interesting. Yeah, you think of a lot of handiwork as producing something with longevity, something that will last, or something with a particular use, like a rug.

Or a table, yeah. I do some things like that—I crochet and I like the functionality of those creations, but even a hat feels like too much commitment for me. I don't know what people want to put on their heads or how big their heads even are. I’ve made so many baby hats that were way too small because I’ve just never had a baby. But a blanket is almost never the wrong size. If anything, it can just be a napkin. It’s kind of the permanent impermanence that I appreciate. Even in those cases, it loses its value over time, but the idea that someone made it, that they chose each part and decided on all of the details, that part remains important.

So what would you describe as your definition of craft? And does it relate to what you make or is that something else altogether?

I would have to describe it as “a practice,” a practice that the person is trying to improve upon. Not only do they have a skill, but they’ve specifically trained that skill. Maybe that's writing or physically making something. I don’t know that it matters. You know, if I line up all the things that I've made in the last year or two, I can definitely see that the drawings have gotten a little better—there’s some dimension there that I didn't have before. I can see that. And it doesn’t change my perception of the older ones, but it does feel like I can watch myself change and that nobody has to tell me their opinion on that fact. I’ve never really had the same relationship to my writing—you know, typically I write something and I never want to see it again. I can’t even assess how good it is because I just can’t look at it. It ages differently. Still, I guess both are trained skills.

Normally, I just keep a little drawing pad nearby or somewhere open in the apartment. It’s almost like leaving out a bowl of nuts. I'm just always walking by and adding a little something here and there. You don't really finish a meal that way, but sometimes a snack fills you up.

That’s interesting. Would you consider your writing practice a craft that you own or what’s your relationship to it now that you have this other thing?

I don't know. It’s kind of like a pair of skis. I don't ski anymore but I own skis, and yeah, if you asked me to, I cloud ski. I have skied. So I feel like it’s a craft that I’m not improving anymore or at least, not in the same way. I'm not sitting down and reading so I can understand how to do the thing myself. I think that's important, that kind of research, but now, that’s what I’m doing with comics and illustrated things. It’s about the challenge of emulating something, testing my capacity to draw something, a shape that I like, a form that’s complex. My grandma was always telling me, “You really have to learn how to draw.” It’s like anything else—there is no other way than to just do the thing.

How has that work made it into the world so far?

Do you feel like your grandma really influenced this particular trajectory?

She taught me a lot of these things–how to crochet, how to knit. I failed utterly at that; it’s always backwards. I do feel the sense that I’m picking things up and carrying them on—I can look at what she did and share in it. I have her drawings all over my place, which is really nice. It’s like having a teacher right there. She was very detail oriented and very precise, but I think she also had a real appreciation for imperfection and that's definitely been a guiding force for me. I don't have to hesitate to try and make something because I don’t have the right set-up or whatever the excuse might be. The imperfections, the things that are missing from my toolbox, they make for surprises.

Do you feel this practice is something you make a part of your day naturally or is it something you have to make time for? Is there ever any tension?

Normally, I just keep a little drawing pad nearby or somewhere open in the apartment. It’s almost like leaving out a bowl of nuts. I'm just always walking by and adding a little something here and there. You don't really finish a meal that way, but sometimes a snack fills you up. As much as I can, I guess I just try to leave crumbs for myself to see if they make a trail.

Do you feel like there are any particular things that spark ideas? I don't know that I would be able to pin-point them either—I’m just curious about your process.

I’m always kind of surprised by how things emerge, whether it's just a name that I hear that sounds funny or an image I come across. Some ideas come from things I might have attempted in a short story that turn out to be much more successful as a cartoon. The same has happened with essays I’ve tried to write. Actually I think “Trash Boss” happened in the reverse order. I had illustrated this zine about finding street furniture and then I was asked to read something at an event I hadn’t even written. So I took something I’d been working on and turned it into something that could exist alongside the zine. It was interesting for me to kind of see how each project had such a different feeling, despite being about the same thing. I definitely liked the personality of the zine more. It wasn't so serious, it wasn't trying to explain anything. You know, you don’t need a whole preamble to a wonky chair.

I like skipping to the point, or at least, that’s what it felt the zine was doing in that particular instance. It was like I started in the middle, and illustrated a single paragraph. This way of making has definitely changed my relationship to ideas, in general. With writing, I was always asking myself if it was something I could sell, if it would be the thing I needed to get to the next, if anyone wanted it. (With a zine, the answer is probably not, but you can definitely give it away.) At least, that’s the way I was working in my twenties and early thirties. But that’s a tough way to exist; then everything is part of a building that you can't even get into yet, and you begin to feel like you’re just waiting around for someone to show up with the keys. Everything becomes potentially very useful or something you never hear back about, and in the latter case, you just never end up writing it.

I went in this direction because I didn’t need anyone’s permission. I didn’t have to do this thing because I had gotten an email in my inbox. I could just do it because it felt right. And I’ve actually been able to share it more with the public because of that. There's a certain immediacy to comics that I just really love, where writing tends to be this long, drawn out thing, with so many people involved at every step. You know, you talk to people who work in book publishing and they're all excited about a book that's coming out in a year and a half. That's no good to me. I’m never gonna remember that.

I'm just trying to be garde at this point. No avant. Just garde.