15 November 2023

Craft as Collective Knowledge

Notes on Craft

I’d love for you to start by introducing your professional practice and any simultaneous creative pursuits you might have.

Frederico Pérez Villoro

I have a background as a designer, but at some point, I stopped characterizing the work that I do as “design.” I reorganized the economics of my practice and the kinds of relationships I had with the people I work with. I think of design and of art, as industries. And the ways in which those industries are organized, the characteristics of their economic structures, are different. So I work as an artist and as a writer and as a researcher. My work studies the social impacts of technology and the relationship between technology and spatiality. But I’m interested in socio-technical expressions that skew the techno-scientific trajectory of Western modern technologies and that are in reciprocity with the webs of life. My recent projects are focused on the hydro-social cycle and the power relationships around the domestication of water.

To your question on things I do on the side of work, I like thinking of my practice and my day to day life as being very much integrated. I'm trying to deprofessionalize myself. I enjoy cooking. Cutting vegetables and the physicality involved in preparing meals for people. I also co-organize with a group of friends a school on theory, art and technology, which we call Materia Abierta. It’s a place where we collectivize our learning impulses and organize space for other groups of people to gather and think together.

Hearing you talk about other people, making with and for them, I wonder how you think of your work in relation to the broader public? To what extent does it feed into your process or vision of a final product?

I was just having this discussion with a writer recently. I argued that the writer-reader relationship is a given that can be considered critically and made explicit in the forms and formats that a text might take—structural, contextual, and social frameworks circulate ideas as part of the writer's practice. This person disagreed and suggested that instead, the act of writing happens as an intimate need of expressivity—that writers would write even if they are not read. They do not intend to be read by others. This is probably true in some cases. Yet I certainly enjoy thinking of the work that I do with the expectation of use, of transformation by other people. But that is probably because I develop tools which are, in many cases, open-ended.

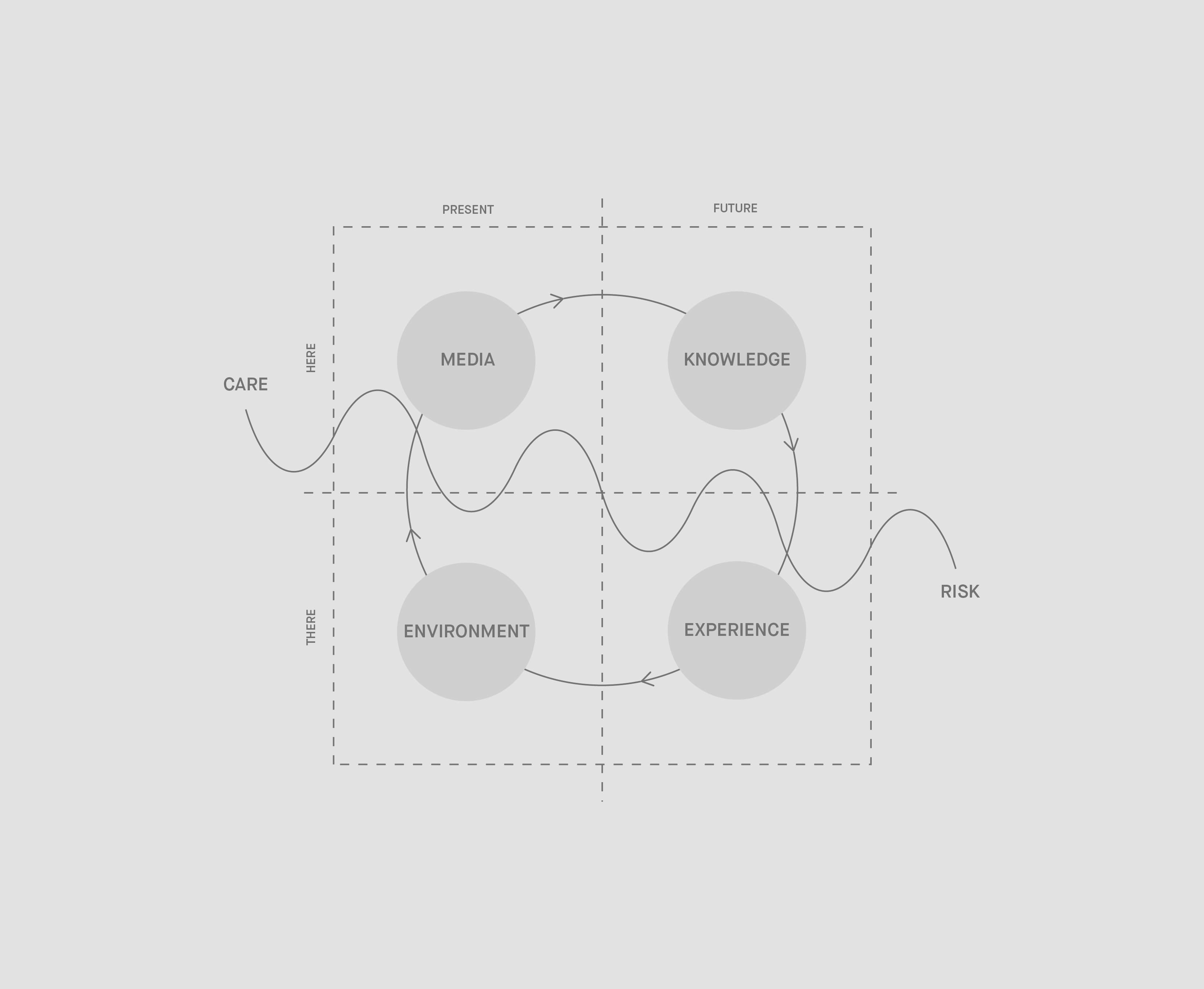

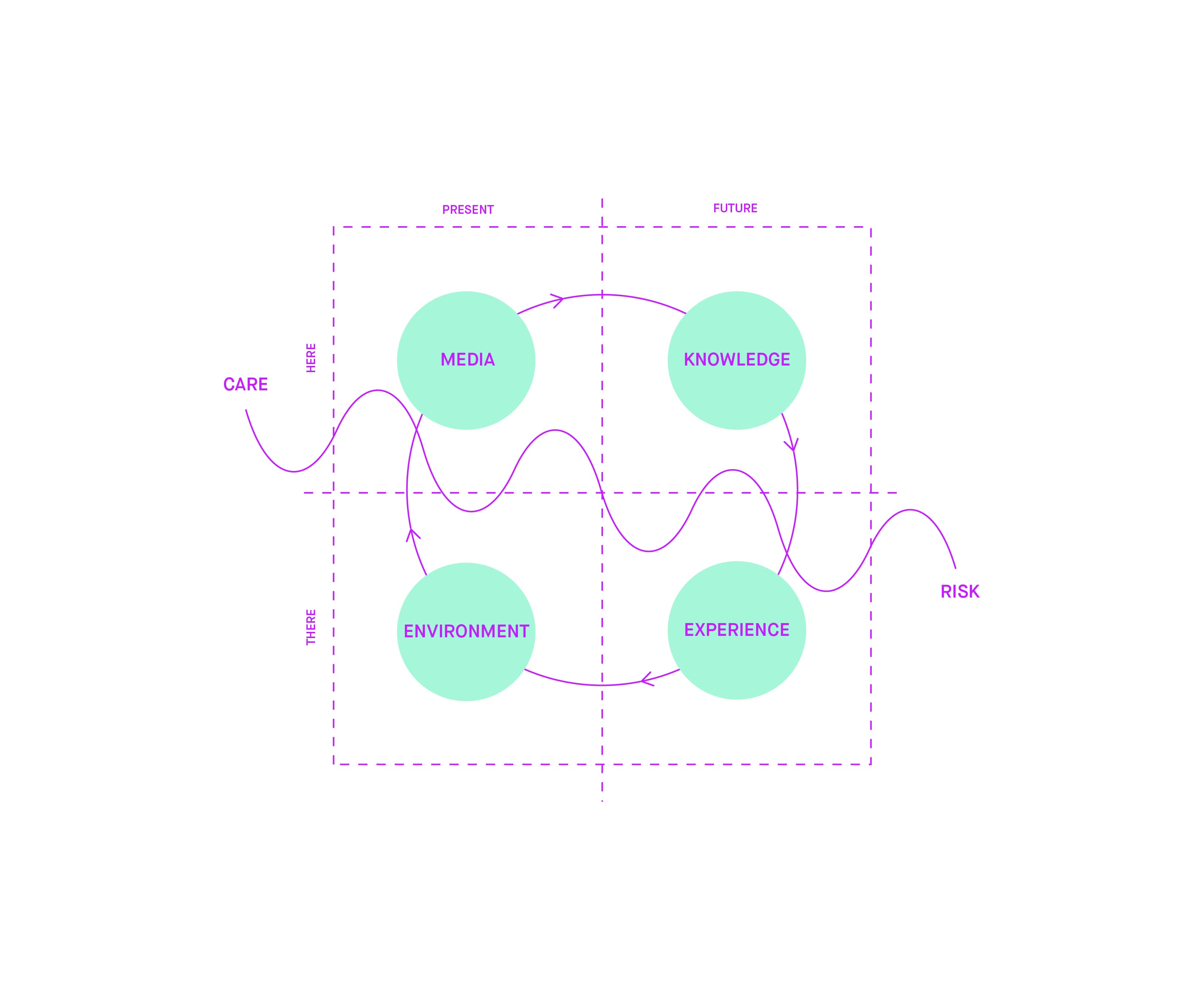

My projects tend to come from a sense of curiosity and a quality of experimentation that often leads me to a multiplicity of knowledge, in plural.

I’m curious how you think of the material output of your work, then, and what kind of relationship to craft it possesses, if any.

I haven't thought much about my work relating to craft specifically but I think the concept, in my immediate understanding, refers to a disciplinary position. That’s probably a shallow way to think about it. But I don’t recognize in my practice such a disciplinary degree of specificity. We can certainly expand the concept of craft beyond disciplines and think about it as having a profound relationship to precise ways of making, and perhaps not just making, but thinking as well. Making and thinking being obviously interwoven.

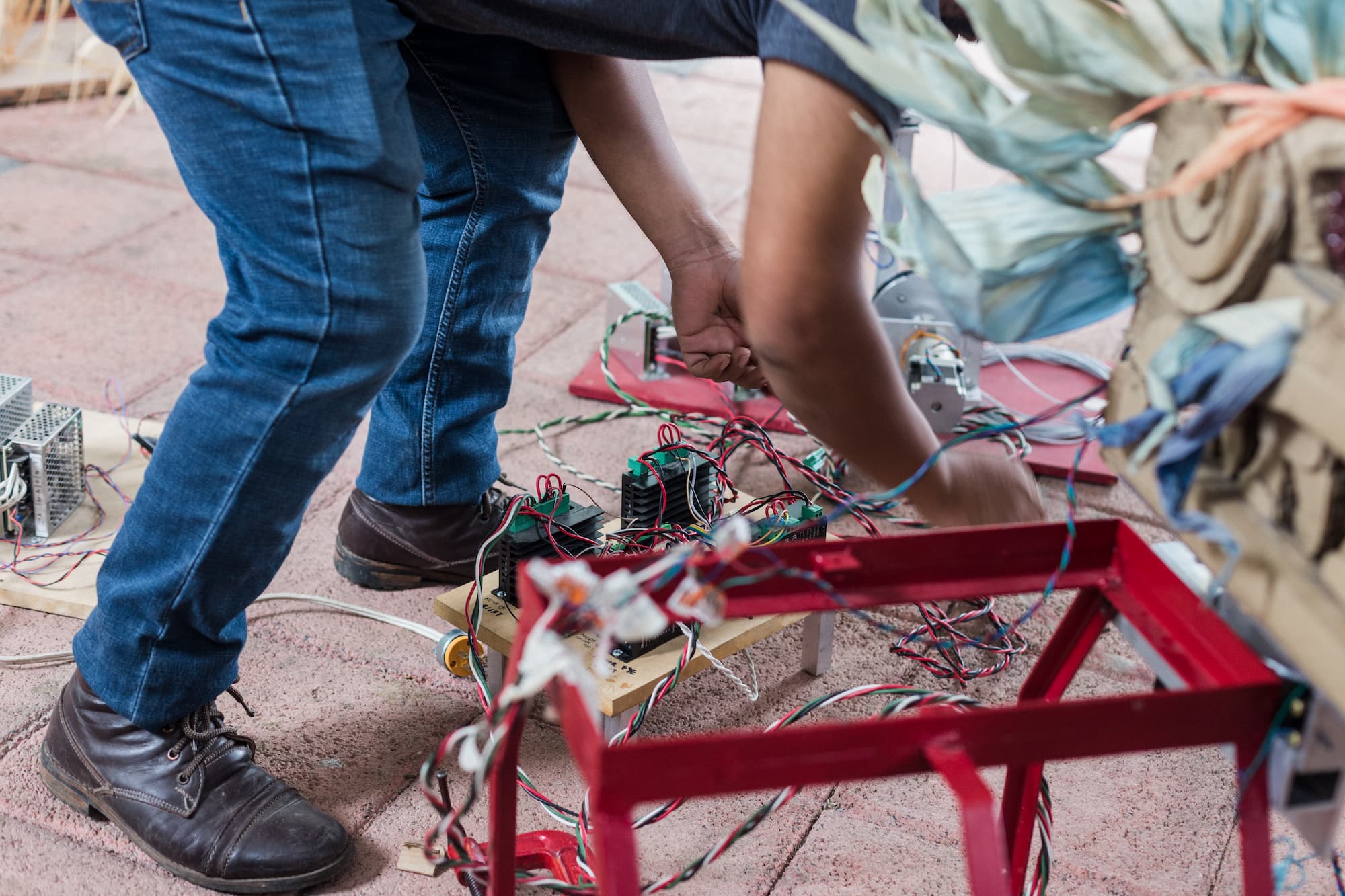

I don't make as many objects. I do installations and create digital artifacts—as ways in which my research materializes itself and is mediated in physical spaces. My projects tend to come from a sense of curiosity and a quality of experimentation that often leads me to a multiplicity of knowledge, in plural. So I tend to collaborate with groups of people—in many cases, people who are “experts” in their field. I work with scientists; I work with technicians; I collaborate with people that have a much more focused relationship to specific fields than I do myself.

There’s material intentionality in my work, but the notion of craft feels limiting if we don’t explicitly amplify it. The concept has a proximity to an anticipated expectation for an outcome that is not yet here. As I’ve learned to collaborate with groups of people, I’ve relaxed my own expectations about outcomes and learned to trust and embrace the unexpected. Projects are just as evidence of processes with multiple inputs and in case little degrees of control.

I think working with other people is a craft in and of itself. I wonder how your notion of the word has been influenced by the relationships you’ve pursued with other craftspeople. Maybe you’ve decided that you can't define yourself by the same terms. In your collaborations, where there seems to be this equal transference of knowledge, how do you see that transference taking place for you? Is something deeply embedded in tradition getting passed down to you in that process?

I have a strong appreciation for people who carry traditions and have a strong relationship to a material culture. Over the years, I have been lucky enough to learn from people that have cultivated knowledge around a specific trade and protect it as a way to acknowledge the histories of places and the extent to which craft is grounded in specific territories.

This summer during Materia Abierta, we worked with Jorge González Santos, for instance, who is an artist from Puerto Rico, Borikén. He runs “La Escuela de Oficios,” or “The School of Trades.” During his workshops, Jorge taught us a weaving technique called “el tejido de soles,” which carries important tales of the colonial violence waged on the Caribbean islands. I was truly inspired by Jorge's deep sense of respect for the fibers that we were working with and the sense of care for trades that stand in reciprocity with the land, but also in the service of memory. The sharing of that knowledge was incredibly inspiring and also provided a strong way to generate space for organizing effectively.

I don’t think that we should attribute our outcomes as designers or artists to our individuality; the same goes for anything else we make ourselves, even when we make it with our own hands, anything we craft.

Sometimes, I think the hand is required for certain forms of communication—it’s an interesting dynamic but certain ideas translate better when we are able to activate our bodies around them. I'd love to hear more about how you initiate a relationship with these individuals. Where does the seed come from—what's kind of driving those encounters?

There are a couple of ways to respond to that. The school that we organize provides fertile spaces to actively seek to collaborate with people that we respect. Having such a social infrastructure has been incredibly nurturing for our team and allows us to develop strong bonds of friendship with other individuals and collectives that are also motivated by the production of knowledge, as something that is grounded, that takes place in specific places.

About an hour ago, I read a post on Instagram by Mujeres de la Tierra, which is a group of women that we frequently collaborate with. They are organized around traditional farming technologies as a way to the defense of autonomous territories in Milpa Alta, located in the south of Mexico City. The post said in Spanish something to the effect of“Mientras más lejos de la tierra, más lejos de la vida” which in English translates to, “The further away from the land, the further away from life itself.” Often these friendships we develop start from certain political or philosophical alignments. We like thinking about the school we organize as going beyond theory and putting in practice intimate political complicities.

In our email exchanges, you mentioned the idea that knowledge can be inherited. I think that’s a profound proposition, actually. It brings to mind a recent encounter with Sameer Farooq. We hosted a workshop with him on flatbread in Mexico City. Sammer built a Tandoor in our studio, which is a vertical oven commonly found in Pakistan—a communal technology that families share within neighborhoods. It’s an oven designed to be pushed around and stored outside. I remember Sameer describing in response to a question about the specific forms the bread takes as the result of him invoking the knowledge that he carries in his body. The movements he makes to amass the bread is not a result of a distinct decision-making process, or even a kind of knowledge that was given to him consciously; it is rather something stored in his spirit, he said; it’s embedded in his physical body. I think that is beautiful way of thinking about the embodiment of craft and the politics of making.

I don’t think that we should attribute our outcomes as designers or artists to our individuality; the same goes for anything else we make ourselves, even when we make it with our own hands, anything we craft. I suppose that could be another thing that differentiates “craft”—it's not something you can do by your own means—it requires apprenticeship, and a disposition to learn with others..