10 November 2023

Craft as Potentially Non-Symmetrical

Notes on Craft

I’d love for you to start by giving a view of your primary occupations, as well as your creative pursuits. Perhaps you can talk about what tension exists there and how you make space for one or the other.

Ariel Wood

My primary occupation is currently teaching—I teach undergrad art courses at a university, primarily in the foundations department. Those students are mostly freshman art majors. This semester, that includes a class about time and technology, as well an Intro to Sculpture class. I'm also teaching an intermediate lithography printing class to juniors and seniors. I’ve been doing this work for awhile now— teaching art—whether to undergrads or adult students at a local art school, where there is a continuing education curriculum.

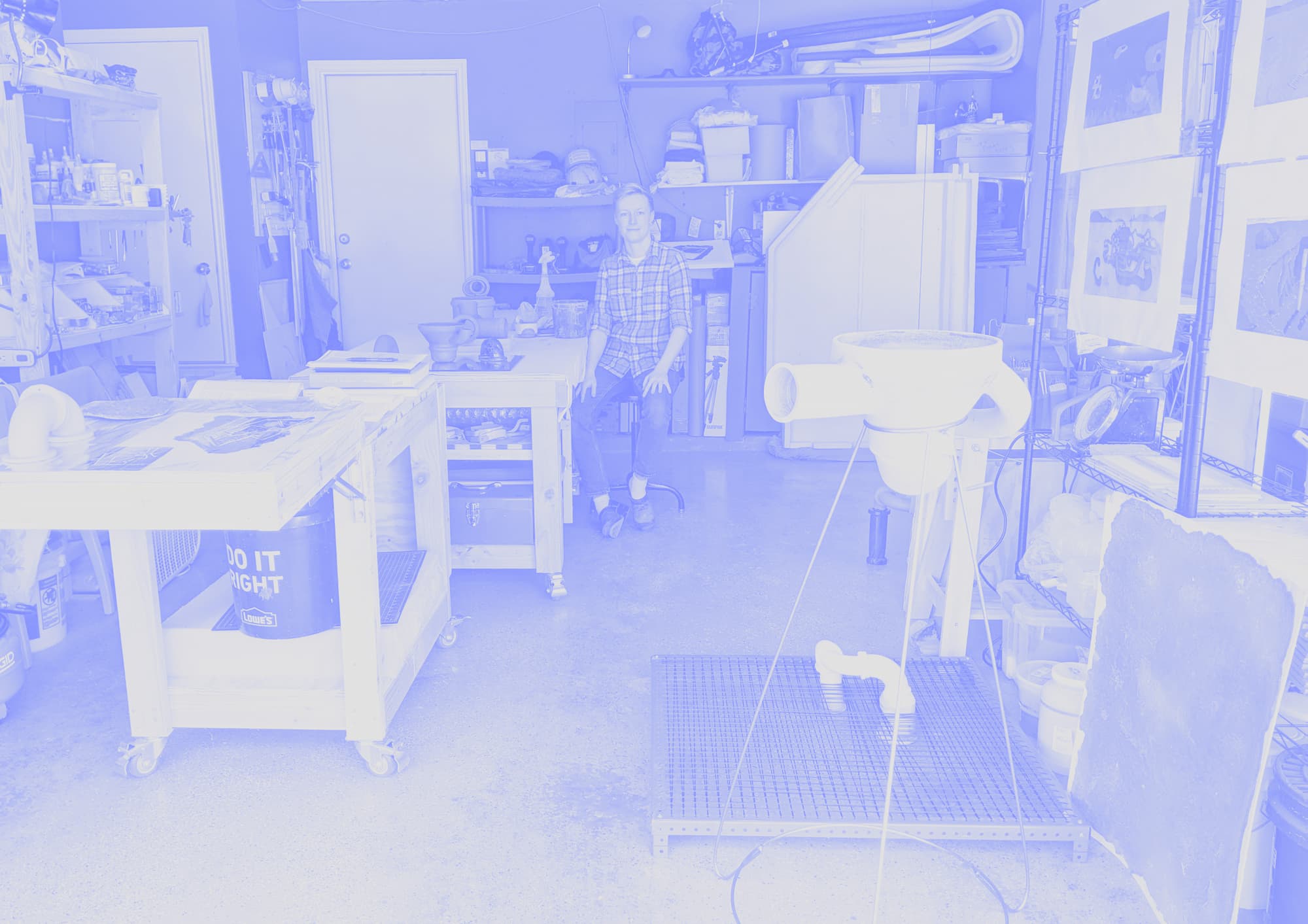

My creative work takes place in my studio, which also happens to be my garage. While the teaching is in the arts, and therefore creative, it is still my primary occupation, and in that sense, isolated from my creative practice. When I am able to make space for my creative work, I have a tendency to feel guilty for not working towards teaching. So “tension” is definitely an apt word—it’s something I feel and relate to a lot.

That definitely sounds like a lot to be juggling with making. Can you speak a little more about the specifics of your creative practice?

I am primarily a sculpture artist working in the fine art realm. My practice involves ceramics, wood, metal, paper mache—a large variety of materials—and involves a range of other disciplines as well. I do etching and lithography when I have access to those things. Right now, I am using large structural systems common to plumbing and drainage to speak metaphorically about the body, queerness, interconnectedness, and things of that nature. I’m often pulling from this system formally—its shapes, its objects, its mechanisms—and placing them in conversation with new material.

I also have a small business making and selling small batch ceramic wares inspired by my love of cooking. This allows me to hone my ceramic skills and explore function and aesthetics outside of a traditional fine art context. It’s really lovely having both ways of operating in clay—it means I never feel hindered in what I make.

How did you find your way to such a variety of different mediums?

Of course, I didn’t just take this pathway for the goal of teaching. I also love art as an artist, but I suppose it gave me direction. I did undergrad at UW Madison in Wisconsin, with a focus in printmaking, and then a post baccalaureate in Italy, which is where I started making sculpture. I worked primarily in that medium before applying to grad school at University of Texas at Austin for an MFA in Sculpture. So I’ve had access to big chunks of studio time and coursework in an academic setting for a good number of years now.

No matter what, it will always be an aspect of the conversation—either you are considering craft and very deeply tied to it, or you acknowledge that it is something you would like to shift away from , or maybe when all is said and done, you land somewhere in between. But we will always find a way to talk about it.

I’m curious if you can isolate anything in particular that led you to that first juncture—to study studio art in undergrad. Do you feel that you had an upbringing that modeled a certain value for art and making? Was there a specific familial tradition of craft you were after?

I loved art from a young age. I think my family is definitely art-minded, but except for my step dad, who happened to be an artist and also a banker, there weren’t many artists immediately represented. Still, it was never something that was pushed out of context, which is to say, no one ever suggested I should pursue something else in school because they wanted to invalidate the idea of a professional art practice. That definitely helped to position me unselfconsciously. And I've always loved learning the process of things, how things are made, and how to use different materials and different styles. Process, I think, is definitely integral to craft, especially as that process relates to tradition or to the quality and expression of a particular formal output. Having those discussions, especially throughout undergrad and then into grad school and now as a teacher, I want to say that craft has always been a very malleable idea to me, even as it’s remained a hot-button word throughout my time in academia.

I can definitely relate to that. I'd be curious to hear your definition of the word “craft,” how that has changed over time, and if it has, whether or not you can locate the junctures at which it did.

I remember I got really excited about screen printing T-shirts before applying to undergraduate programs. And I sort of decided that’s what I would be as an artist—I would make T-shirts. I decided to attend UW Madison because they were top in the country for printmaking at the time. And the closer I got to printmaking, as I really started looking at it, I saw how detail-oriented it was, and I began to think of craft as reliant on that quality—it was very technical, and incredibly attuned to drawing expressively. And I was excited to hopefully hone those skills, to really lean into those technicalities. But throughout my time there, as I started taking art history classes, I began learning about and looking at different kinds of contemporary art, which seemed to be more and more removed from those specificities of craft I mentioned before. And in the process, I got really excited about minimalism—I liked the material openness of it. It didn’t feel so austere. I still saw craft as present in that context however. I suppose the definition became less about someone's genius or their incredible artistic abilities and started to relate more to their intentionality and care. And then in grad school at UT, craft seemed to be increasingly pushed away. They basically cut off their ceramics and metal-working departments with the supposed hopes of making sculpture more seriously conceptual and contemporary. So I found myself in the midst of this big pedagogical shift in the department, relating to this concept of craft.

All that's to say, “craft” is a word that's hard to pin down at any given moment. But I think it definitely has a place in the fine arts and I think it might just come down to the particular intentions of the artists themselves, and the extent to which they want to model “craft” in their practices. No matter what, it will always be an aspect of the conversation—either you are considering craft and very deeply tied to it, or you acknowledge that it is something you would like to shift away from , or maybe when all is said and done, you land somewhere in between. But we will always find a way to talk about it.

Where do you feel like you land?

I think I land somewhere in between—I want the work to be interesting and engaging and exciting beyond the level of craft. I guess I don’t want my attention to craft to be the primary response of a viewer—to have them say, “Wow, that must have taken so long.” I guess that’s the reaction I often have when I see pieces where craft seems to be the primary motive.

That’s interesting—it’s definitely one of those words that has evolved so much over time. But the idea that craft isn’t integral to concept just feels a little disillusioned to me. I was curious about your mention of care—that’s something that I think about a lot, in relation to an activation of “craft.” Is that something you try to define in your own practice?

I'm glad you pulled that out—in these conversations that I've had about craft with artists and critics of art, the general populace or what-have-you, there's often an immediate dismissal of it. But I think it has such a wonderful possibility. To ignore all of the people that have come before—if there’s a whole tradition and a thoughtful process involved in a particular practice—to just brush that aside, to have an entirely intellectual, theory-based approach to your work, to consistently imagine yourself reinventing the wheel, is kind of ignorant. Maybe you're creating a lot of waste or doing harm to the environment. Whatever the context might be, to approach your material without any consideration for how it’s been used in the past feels misguided to me. You give more agency to the material when you consider how it’s previously been used. That’s a form of caring, I think.

I’m also curious if that care comes into play when you consider your audience or concept that the public reads that is there something you would consider as part of your approach there? Is that a different kind of conversation that you're having?

I definitely want to care for the audience. But I’m not sure how often that comes into my consideration or attention for craft. As I said before, I worry that highlighting craft too much restricts the audience from stepping outside its boundaries. Sometimes, when an object is so meticulously executed, I think it creates a distance between itself and the audience. I'm really interested in the ways that making or remaking certain objects by hand—in my case, the heavily defined, structural elements particular to plumbing—allows them to become non-symmetrical, non-functional, non-fill-in-the-blank. This slippage is where I see moments of non-craft, which is not to say, those things are the opposite of craft, but they don’t model perfection. I think things might lose their humanness when perfection is primary.

Yeah, that release of control can be really freeing. What do you think is the destiny of those objects—is there a perceived, or idealized life to those things?

I haven't thought about that question in a while because I think I'm so heavily focused on their life pertaining to the space of the exhibition. Most of the things I’m making at the moment are in preparation for a show. Sometimes, I’m making tests or doing other small-scale experiments—the destiny of those things is maybe in the form of knowledge, knowledge that leads to some other formal output. But most other things are destined for the exhibition. As a sculpture artist, what happens after the show is always a somewhat embarrassing moment, where I’m shoving the work into a storage unit or dismantling it into a dumpster. But, who knows—maybe someone will want it in their living space or collection at some point along the way.

Is there any particular community that you feel like you are making work for or do you feel the work is more for yourself?

I do think I make work with the public in mind. . I’m really interested in the writings of Gordon Hall and other queer theorists on the subject of abstract art—how objects can change people's way of looking at the world and interacting with specific groups of people. That’s always a throughline in my practice, that conversation with the outside world. But most of the time, I am more intentionally making the work for me, which ends up having a kind of specificity that other people can access and relate to more naturally. I think, if I always had an audience in mind, I might end up closing off the possibility of other audiences. It might narrow the entry points.

I think about craft with regard to discipline and the ability to show up everyday for something. That idea can be quite abstract to the majority of people. What makes you show up for yourself in that way? Are there moments when you find that your can’t?

I definitely don’t have a consistent, daily practice. I suppose I have a lot of other things in my life that fulfill me in that way. I really love cooking and gardening and things of that nature. And while my art practice is so close at hand—it’s wonderful to have it in my garage, just outside my door—I think the making takes place in big bursts, and in smaller sporadic time periods. My love for this stems from a lot of things—working with my hands, the immediacy of feeling through the world—these affinities are kind of innate and I can’t really imagine not having the space to do them, not wanting to show up for them in some way. But it’s also about putting these materials into conversation with other people and the way that abstract objects can give us room to explore non-abstract ideas. I think art can facilitate those conversations in really interesting ways.

When the work arrives in the exhibition space, I really enjoy the interaction with the person encountering the work for the first time, who says, “Wow, you really changed my mind about something.” I have so many people sending me images of plumbing now. I love this—the fact that people are now noticing this thing that would otherwise go unnoticed. Not that it’s all because of me by any means, but the minor shifts the work can create are really satisfying moments for me.

I'm interested in the ways that making or remaking certain objects by hand—in my case, the heavily defined, structural elements particular to plumbing—allows them to become non-symmetrical, non-functional, non-fill-in-the-blank.

It's so fun when that happens—you have some narrow area of focus and suddenly everyone sees what you're seeing. So how was it that you landed upon plumbing?

I think it was a lot of different things. I moved out to Texas for grad school, as I mentioned, and everything here is big. That's what they say, actually. So I started noticing certain kinds of infrastructure in a way that I hadn’t before. The rain comes down really hard and really fast here, so stormwater is handled differently. Its infrastructure is big and seemingly everywhere. I got kind of absorbed by its hyper-presence, its hyper-visibility. And then I encountered Robert Gober's “Drains,” which had a really big impact on me. I liked the way his practice meticulously reacted to objects. He had made a couple of different pieces with drains and sinks that really piqued my curiosity.

Ceramics was the final element layered into these discoveries. It was a rather essential part of the mixture actually. I was throwing on the wheel, where everything becomes symmetrical and inherently connected to these forms in our built environment. There are actually tons of artists working in wheel thrown ceramics, making plumbing pipes, at this point; something I discovered later, but find engaging and an exciting conversation to be a part of.

How do the specifics of your practice feed into your teaching? Is there some sort of angle that you feel you have on that now; do you see those things communicating often or not so much? You said that they felt too connected at times and I’d love to hear you talk a little more about that.

The fact that we're not required to have any teaching certificates—that has its pros and cons—it also means that I’m constantly worried I'm not doing my students justice. I worry about what I don’t know, or about my biases towards the things I do know, about the work I like and what I choose to share with them because of that. It’s definitely a challenge, a constant tussle. However, I do have experience in a real range of materials and I think that is a benefit to the students. Hopefully, it benefits my teaching too. Over time, I think I’ve allowed myself to be more focused on meeting the students where they are—we all come to the work with different personal experiences and interests and formal affinities. I try to avoid giving the students a sense that there’s a right way and a wrong way—that certain art forms are inherently better than others. It’s about what they want us to experience from the piece—if we’re getting something they don’t want us to get, then maybe that's something to think about.

I guess that’s a good lead into a question about starting something—how do you know or realize the content of your writing? Is that something you pursue consciously? Or is it more spontaneous than that?

Yeah, I wish there was some sort of secret generator—I have a project I'm working on now and I’m asking myself, “What’s the next thing?” And it really feels like there is no next thing—like I'm never gonna write again. And then somehow it just accumulates—I think from years of just living with the sort of mind that’s attentive to writing and thinking about what experiences could turn into something. Then those things start to add up and connect to each other. And it all just kind of happens. Sometimes I write a smaller essay—that’s what happened with the book and with this next project—I write an essay and then I just keep writing toward that topic. And things accumulate, but it takes so damn long. That’s the tough thing about it. The time.

Do you wanna talk about your book at all? The one that's coming out in the Spring.

Yeah, everyone smash that pre-order link—July 16th, it’s coming out.

I think I started writing this book seven years ago, so it’s not as if it was the only thing I was writing. I didn't really work on it much in grad school except for during my thesis. But it’s accumulated over time, and is now a book. It’s about my professional soccer career and my relationship with soccer and with sports and gender and aging and time passing. I should get better at talking about this—this is really the first time I’m talking about it in an interview. I guess it’s also a study of books and writing and art in parallel to that. Actually, it’s a lot about craft too—craft of elite athletics and craft of writing and how those relate to each other—it took me a long time to acknowledge that they did.